Artificial Intelligence (AI) is reshaping industries at a remarkable speed. However, its rapid rise has sparked bubble-like behaviour. Extreme valuations, trillion-dollar spending plans, and circular investment flows hint at speculative excess — but transformative technologies often begin this way. For investors, the challenge is not predicting the future of AI but identifying durable businesses that benefit from AI without paying bubble-level prices. Ben Preston, portfolio manager at our offshore partner, Orbis, explains.

Key takeaways

- Bubble dynamics: A defining feature of market bubbles is the feedback loop between management ambition and investor capital. Today’s AI boom shows similar traits – surging spending, sky-high valuations and a heavy reliance on investor funding rather than customers.

- Stacking the odds: Forecasting winners and losers is notoriously difficult; even extreme valuations can precede extraordinary returns. Rather than trying to call the top, investors can stack the odds by owning well-run, cash-generative businesses with robust economics across multiple outcomes.

- Selective exposure: AI’s promise is real, but so is the risk of overpaying. Selective positions in firms like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), Nebius, and Samsung enable us to capture the structural benefits of AI adoption without the speculative multiples that often accompany bubbles.

A hallmark of any self-respecting stock market bubble is not just the dramatic rise in share prices, but also the surge in corporate spending. It’s that coalition between managements eager to grow and investors cheering them on with ever-larger infusions of capital that lays the groundwork for future disappointment. When managements go too far – giddy on easy money and optimistic forecasts – they sow the seeds for a bust created by their own overexpansion.

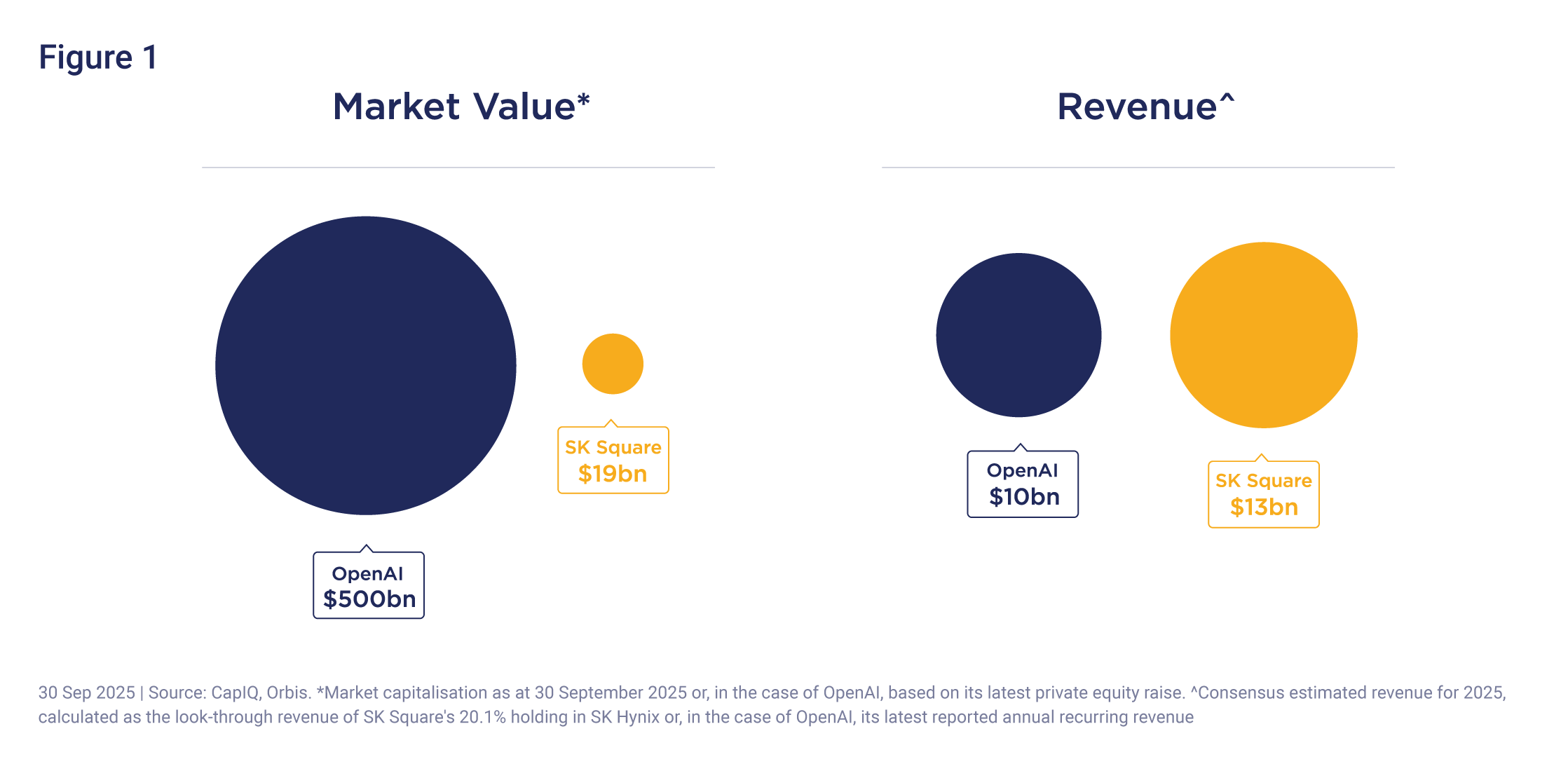

That risk looms large today, given the enthusiasm around AI. OpenAI, for instance, is being valued at US$500 billion in private markets, making it one of the world’s most highly valued companies despite generating revenue comparable to a mid-sized US regional bank. It has made eye-wateringly large spending commitments totalling over a trillion dollars, while expecting to remain cashflow negative for at least four years. So far, vastly more of its money has come from investors than from customers. Add in the circular money flows – the “infinite money glitch” – between the likes of OpenAI, Nvidia and Oracle, and alarm bells should be ringing.

Yet the technology behind AI looks genuinely transformative. Proponents describe the transition from “generalised computing” to “accelerated computing” as being as significant as the commercialisation of electricity or the shift from horses to cars. Adoption remains at an early stage relative to its full potential.

The headache for investors is that the same ingredients that often characterise bubbles – high share prices, rapid expansion before profitability, and extravagant forecasts for unproven demand – can also describe an emerging investment trend that’s too important to miss. How, in advance, can one tell the difference between a dotcom bubble featuring disasters like Global Crossing and pets.com, and a digital revolution that produced Apple, Netflix and Amazon?

The headache for investors is that the same ingredients that often characterise bubbles, can also describe an emerging investment trend that’s too important to miss.

Hindsight always makes it look easy, and after the dust settles there will always be those taking victory laps for having called it correctly. But if it were truly easy, everyone would see it, and bubbles would never form. Apart from at “extreme extremes”, making those big market calls is surprisingly hard. There is no single metric that provides certainty. In 2002, after the dotcom bust, the CEO of Sun Microsystems famously chastised investors for having paid “ridiculous” multiples of 10x revenues just a few years earlier. Any investors who heeded that warning would have struggled to buy Nvidia at the same valuation twenty years later – and would have missed returns of 2 700%.

The future is inherently unknowable. History is a useful guide, but it’s far from perfect because markets are dynamic and learn just as quickly as investors, if not more so. While not perfectly efficient, they’re very good at pricing shares at a level that makes decisions difficult.

If that uncertainty feels uncomfortable, take heart: nobody knows what the future of AI holds – not even its creators. The playing field is more level than it appears: We’re all operating in an environment of unknowns.

More encouraging still, successful investing isn’t about predicting the future. While a crystal ball would no doubt be useful, investors can do exceptionally well by focusing bottom-up on companies with sound economics, outstanding management and valuations attractive across a wide range of possible outcomes.

Investors who assemble a portfolio of such businesses stack the odds in their favour. Fortunately, we’ve been able to buy shares in companies that have turned out to be clear beneficiaries of AI – such as TSMC, Nebius and SK Square – without having to pay the bubble-level multiples that come with significant downside risk, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Looking ahead, we expect the same disciplined approach will allow investors to continue to find opportunities to gain exposure to AI’s potential, without taking a directional bet on whether it will prove the most transformative innovation or the biggest bubble in history.

“Successful investing has little to do with predicting the future. It’s about discipline — owning quality businesses at attractive valuations across a range of possible outcomes.”

Artificial intelligence is real, and it will change the world – perhaps in ways we can’t yet imagine. Whether today’s early leaders will dominate or collapse dotcom-style, paving the way for new winners to emerge from the ashes, remains to be seen. But by staying close to the ground, remaining adaptable, and assessing each company on its merits, we believe the hunting ground will remain fertile for bottom-up investors seeking to buy companies for less than they’re truly worth.

This article forms part of Orbis’ Six courageous questions for 2026. Explore more insights from the series:

- What if the real American exceptionalism now lies beyond America’s biggest stocks? by Simon Skinner

- Is the world’s safest currency actually the riskiest? by Nick Purser

- Are you swimming in the right water? by Graeme Forster

- Which risk runs deeper: owning or avoiding emerging markets? By Stefan Magnusson

- What if Trump is right? by Alec Cutler