Unaffordable food and fuel prices are raising developed market consumer inflation to multi-decade highs, while the Federal Reserve recently announced a 50-basis point hike in US interest rates from record lows. Thalia Petousis, portfolio manager at Allan Gray, discusses what this may mean for South African investors in terms of inflation, bonds and more.

Food price inflation is a powerful force precisely because it impacts the consumer so directly, making it an intensely political phenomenon that governments and central banks cannot ignore – or can do so at their peril. In the 1970s when US food inflation reached 20% year-on-year, housewives began organising rallies in protest, ultimately staging a week-long boycott of meat. It is no surprise, then, that when Jerome Powell, the current chair of the US Federal Reserve (the Fed), raised interest rates this month, he began his speech by saying, “I’d like to take this opportunity to speak directly to the American people”.

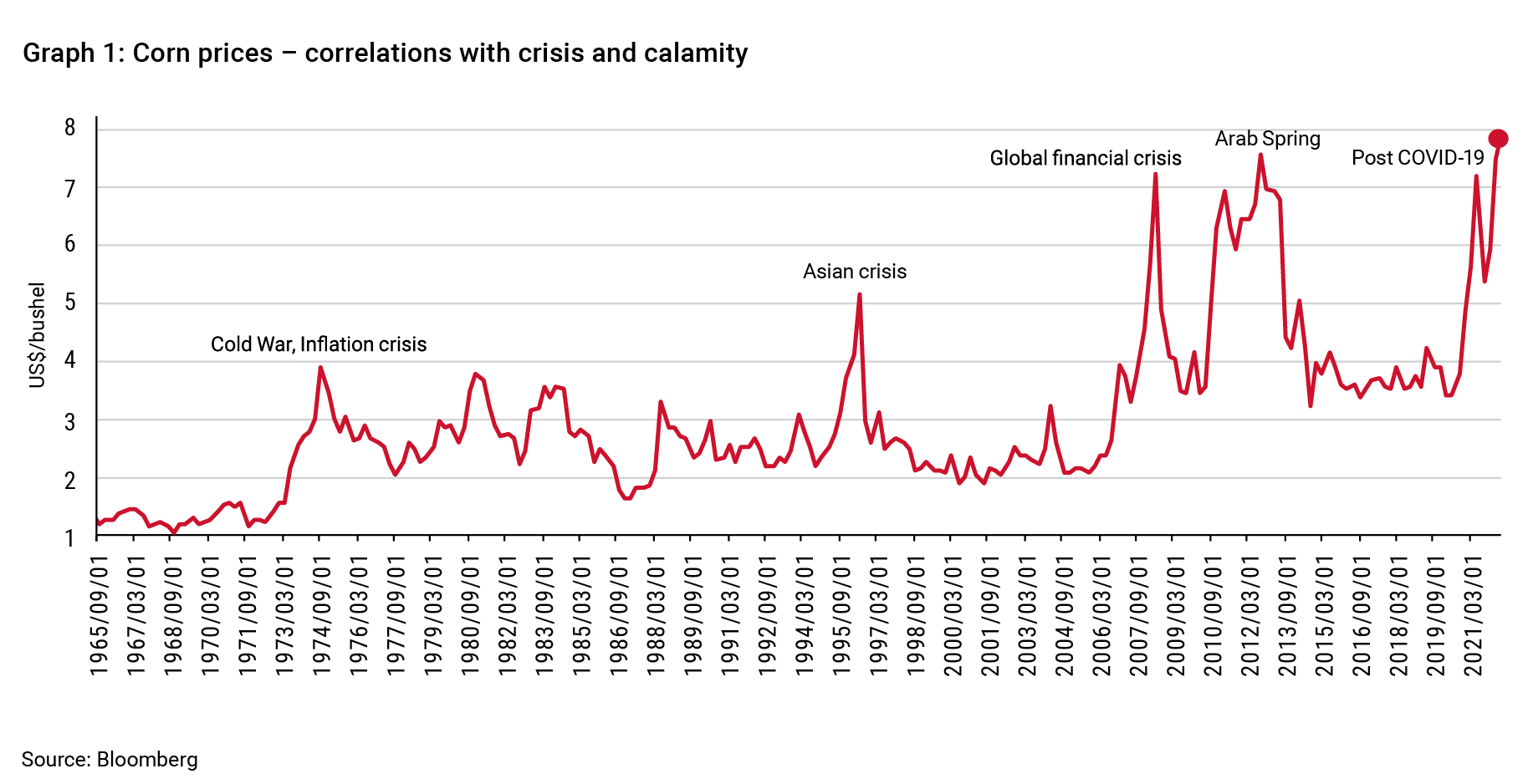

When food inflation gets “too high” in emerging markets, it is not uncommon for regimes to be overthrown, alongside riots and famine. Graph 1 reflects the trajectory of corn prices, which is arguably the world’s most important food crop. In Egypt, it was “bread riots" that were the catalyst for violent clashes that culminated in the Arab Spring of 2011. Fast forward to the present year, and truck drivers and farmers have blocked the streets of Madrid in protest, with citizens calling for a change in the centre-left government as the answer to unaffordable fuel and fertiliser. Sri Lanka is in a severe state of emergency after crop failures have led to food shortages and civil unrest.

Both locally and internationally, we have already seen the return of some element of food rationing – most notably in sunflower oil – to deal with supply chain shortages. Many parts of Europe are seeing producer price inflation of 25%-30% year-on-year. Store shelves in the UK, Italy, and Spain are increasingly light in a multitude of items, and retail suppliers have begun to apply force majeure to major food retailers, scrapping contracts in an unprecedented fashion. The alternative for these suppliers is financial ruin.

Global food inflation was already high in 2021, but not quite near the levels of previous food crises. Post-pandemic consumer demand, tight labour markets, phenomenal US money supply, underspend in gas and oil projects, and a lower fertiliser supply from China are just a few factors that came into what may be thought of as the “2021 inflationary equation”. With war hitting the Russia and Ukraine complex in 2022, the supply chain has been thrown into havoc. The year-on-year price increases in wheat, oil, gas, and fertiliser in the 12 months to end-March 2022 are each north of 70%.

US consumer price and food inflation were recorded at a still-palatable 8.5% and 8.8% year-on-year increase respectively in March 2022, but we must keep in mind that these are backward-looking indicators at the store shelf-level that measure the value of goods previously produced and processed. It took just nine months from March to December of 1973 for US consumer food prices to rise from a forgivable 5% year-on-year to a crisis-level 20% year-on-year. Are we in a similar waiting period now?

South Africa’s inflation is lagging the developed world

There have been only a handful or so of times in the last 40 years that South Africa’s inflation has lagged that of developed markets like the US. Now is one of those times.

South Africa did not have the fiscal headroom to support consumers to the degree that the US did in 2020 via stimulus cheques and grand infrastructure spending programmes. As such, our consumer spending on goods has been far more muted, which means that our demand-side inflation is lower.

US monetary and fiscal policy have been imprudent, but I cannot say that our consumers are in an infinitely better position. SA has been no stranger to stagflation (low growth and high inflation) for several years, and we continue to suffer from severe unemployment.

Where to from here for interest rates?

Developed market central banks need to raise their inappropriately low interest rates if they have any hope of curbing demand, stimulating some form of recession, and taking a bite out of inflation. The Fed will also need to curtail its balance sheet, which has increased in size by 20% in the last year alone as it supported asset prices via massive bond purchases. This will involve extricating itself from the US treasury market, which is no small order – the Fed has been the single-largest buyer of US treasuries since the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020. One year of balance sheet run-off may mean reducing asset purchases by US$1-trillion, or 5% of GDP.

This month, Powell delivered a 50-basis point hike, taking US interest rates close to 1.00%. This is a tiny step in the right direction, but we need to keep in mind that the last time that US inflation was as high as it is today, we are looking at a period of history when interest rates were north of 15%. To call Powell’s 50-basis point move “Volckeresque” (a throwback to Paul Volcker’s interest rate hikes to 15%-20% in the period of the 1970s and 1980s) is grossly overstated.

The impact on South African bond markets

The tightening of the Fed’s spending has the potential for large spillover into international bond markets and has precipitated the recent move in SA 20-year bonds to a rand yield north of 11%.

If US inflation is at 8.5% and the market expects US overnight rates to reach 3% by the beginning of 2023, where should the US 10-year bond be trading for willing investors (i.e., not the forced hand of the Fed) to buy up the debt of the US government?

In a disorderly rise in developed market bond yields, SA’s rates markets will not be immune. Due to the size of our fiscal deficit, we do rely on some element of foreigner participation in local bond markets to fund our national expenditure, and capital outflows may raise our debt service costs further.