Emerging markets (EMs) account for more than 80% of the world’s population and more than half of its gross domestic product (GDP), but less than a tenth of typical global equity portfolios. With cheaper valuations, weaker currencies and lower correlations to developed markets, selective exposure to EMs can add diversification and resilience when it matters most. Stefan Magnusson from our offshore partner, Orbis, discusses.

Key takeaways

- Valuation risk: Developed markets appear safe but extreme valuations and concentration in US mega-cap tech mask hidden risks. History shows that starting valuations at today’s levels have delivered only low single-digit returns over the following decade.

- Attractive discounts: Emerging markets trade at steep discounts – nearly 60% cheaper than the US and with undervalued currencies – offering visible risks but positively skewed return potential. From these starting points, history suggests forward returns ranging from low single digits to 15%+ per annum.

- Weighing up the risks: Avoiding emerging markets may be the greater long-term risk, as broader exposure enhances diversification and reduces volatility. Less coverage, inefficiencies and overlooked compounders also create fertile ground for active managers to generate alpha.

In investing, measures of risk are often expressed as a single number. Calculations of metrics such as volatility, tracking error and value at risk are learnt and memorised by many aspiring young financial analysts, ready to apply their newly honed tools to the world of financial markets.

While some of these metrics may serve a purpose, they can also mask the true risks in markets and provide investors with a false sense of security.

For EMs, traditional risk measures don’t paint a pretty picture. Over the past 15 years, returns from EMs have severely lagged their developed market peers, and have also been more volatile. For a rational investor with a reasonable level of risk aversion, EMs have been an uncomfortable place to invest.

By contrast, backward-looking risk measures point to a much smoother ride for US stocks. Returns for investors in the US stock market have been much more rewarding and have come with relatively lower volatility. It appears that for the average investor, the US is a much more comfortable place to be. But that comfort may prove to be an illusion.

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” – Mark Twain.

The US now makes up two-thirds of the world equity index, carried by a narrow handful of mega-cap technology companies. Investors appear to be comfortable crowding into these few stocks and appear certain that growth will continue.

But the risk that most investors seem to be ignoring, which is masked by aggregated risk metrics, is in the valuations. On a cyclically adjusted basis, US shares on average trade at 38 times earnings, a near-record high.

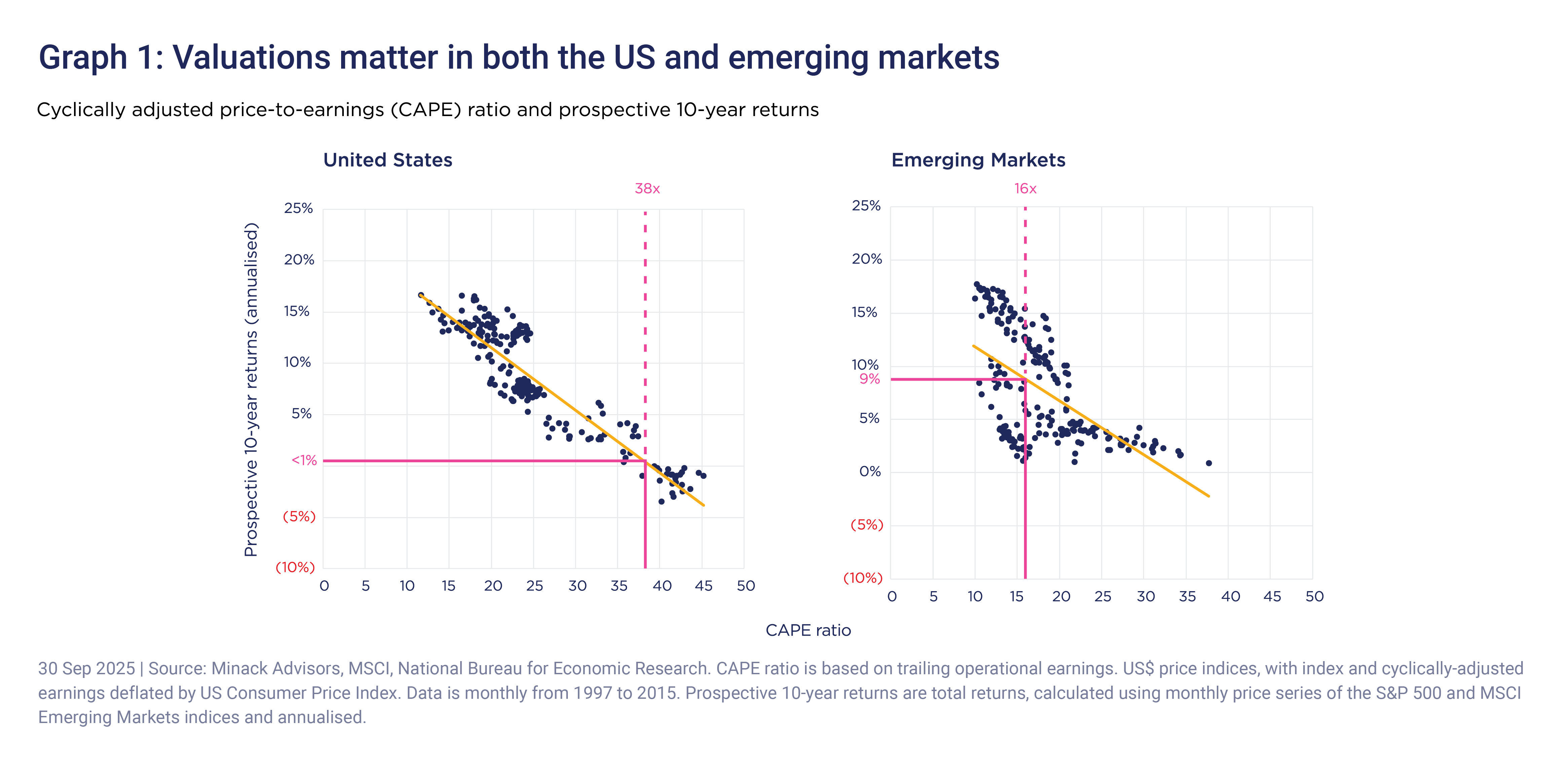

Why do these valuations matter? Because they heavily influence forward-looking returns, as shown in Graph 1. When US shares were valued at this multiple historically, they reliably returned just low single-digits nominally over the next decade, barely keeping up with inflation.

By contrast, shares in EM companies today trade very reasonably. EM shares change hands at around 16 times earnings on the same basis, below their long-term average and a steep 60% discount to the US. The currencies look cheap too, with a basket of EM currencies currently close to a 20% discount to the US dollar based on a simple purchasing power parity model.

For EMs, the range of outcomes for the future is wider but skews more positively, with returns from today’s valuations typically ranging from low single digits to more than 15% per annum.

60%: The approximate discount at which EM equities trade compared to their US peers.

None of this is to deny EM risks. Political instability, deficient governance and state involvement are real challenges, and currency swings can magnify volatility. But these risks are visible and, in many cases, already reflected in depressed prices.

Meanwhile, government shutdowns, ballooning deficits and debt, government involvement in the private sector, trade policy uncertainty and the dollar having one of its worst years in decades appear to have had little to no impact on valuations in the US.

With valuations where they are, to us, not having enough EM equity exposure may be the deeper risk.

Long-term allocations

Often, investor enthusiasm in EMs is narrow and short-lived. In the 2000s, BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) became shorthand for the unstoppable rise of EMs. Investors were ultimately let down as valuations and governance risks reasserted themselves. Today, India has once again become an investor darling, with excitement about its impressive economic trajectory and favourable demographics. But the evidence doesn’t back up the sentiment. In one of investing’s great ironies, there is no reliable link between overall GDP growth and equity returns.

High-growth economies often disappoint equity investors if starting valuations are high, competition increases or poor governance undermines minority shareholder rights. On the flip side, slower-growing economies can deliver excellent returns if shares are cheaply valued. India today trades at a 100% premium to other EMs. Those expectations are hard to meet, never mind exceed, perhaps part of the reason India has been left in the dust by markets like China, Korea and Brazil over the last year.

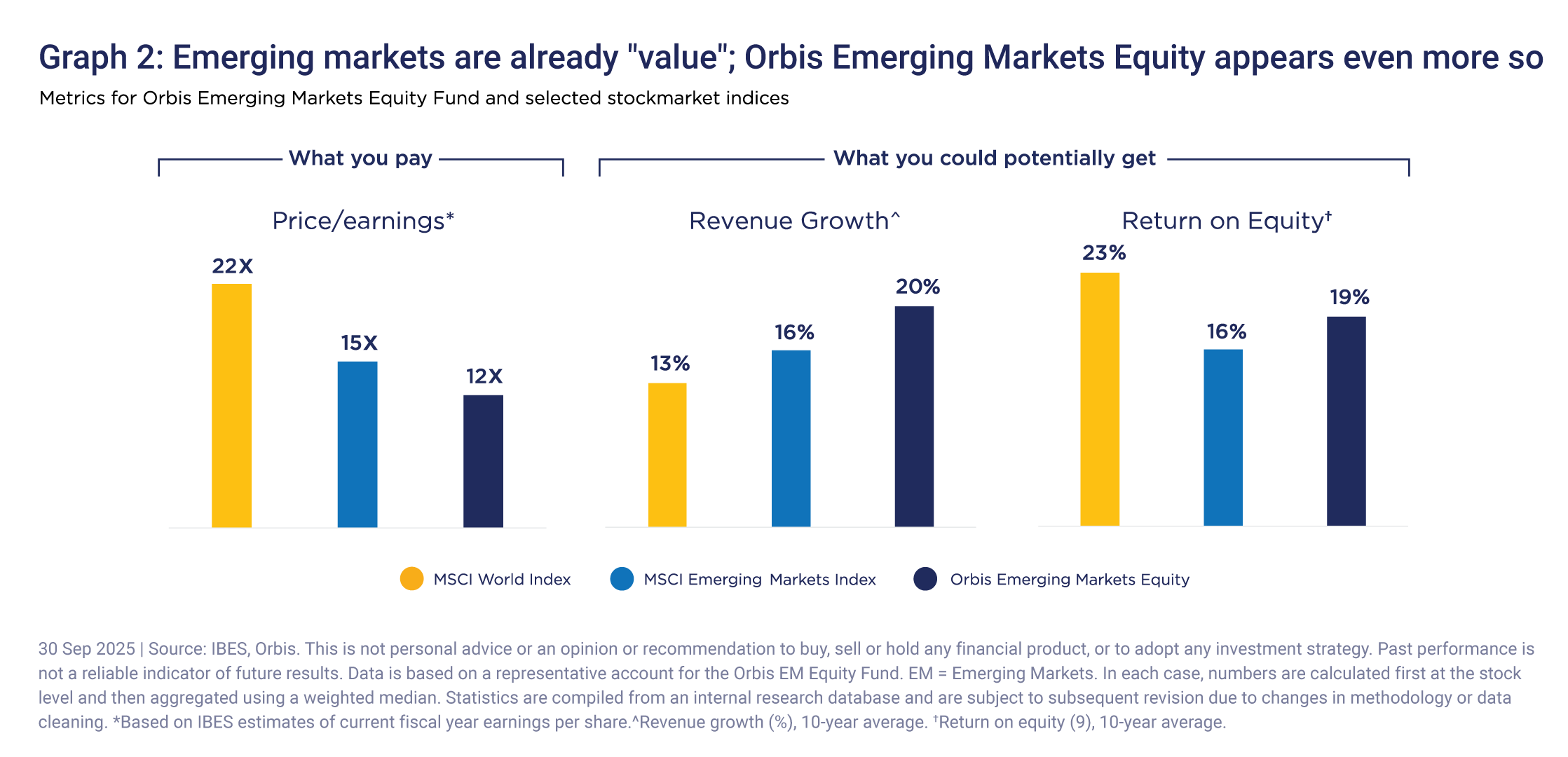

What to do instead? Broader EM exposure, for example through passive exposure, captures a better diversification benefit with less valuation risk. But, as with developed market indices, EM indices are similarly concentrated. China and Taiwan make up over 50% of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, of which 11% is in a single stock, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

A passive approach misses the exceptional alpha opportunity in EMs. EM shares often have less analyst coverage, benefit from specialised local on-the-ground research to address challenges like language and governance, and offer a higher proportion of compounders (excellent businesses with very long-term growth potential). For disciplined investors, this is rich ground for finding opportunity.

Many of the usual risks associated with investing in EMs can be mitigated, if not sidestepped entirely, by being selective. Seeking out EM businesses that are durable, have wide and growing moats, long runways for growth, and able management that is aligned with shareholders can prove highly rewarding.

Breaking the comfort trap

Emerging markets are often avoided because they feel uncomfortable. Volatility, politics, governance – these risks are real, and investors can point to headlines that justify their caution. But in investing, comfort comes at a cost. Global stock markets today carry hidden risks in the form of high valuations, narrow leadership and excessive concentration.

By contrast, EMs offer visible risks at visible discounts. They bring diversification, compelling forward-return potential and fertile hunting ground for active managers. At today’s prices, the deeper risk may not be in owning EMs, but in avoiding them. The comfort trap is seductive – but breaking free of it may lead to stronger, more resilient long-term portfolios.

This article forms part of Orbis’ Six courageous questions for 2026. Explore more insights from the series:

- What if the real American exceptionalism now lies beyond America’s biggest stocks? by Simon Skinner

- Is the world’s safest currency actually the riskiest? by Nick Purser

- Are you swimming in the right water? by Graeme Forster

- Is AI a bubble, or is the best yet to come? by Ben Preston

- What if Trump is right? by Alec Cutler