For decades, global markets revolved around export-led growth and the gravitational pull of US assets. Now the currents are changing. Graeme Forster, portfolio manager at our offshore partner, Orbis, explains why domestic investment and fiscal expansion are reshaping the capital cycle, potentially marking a new era for investors and markets outside the US.

Key takeaways

- The tide is turning: For more than a decade, mercantilist policies and capital inflows into US assets created a self-reinforcing cycle that rewarded many investors. However, as US policy turns inward – marking a structural shift in the old regime – many investors could be caught off guard.

- Repricing underway: Non-US assets and currencies remain historically cheap, but fiscal expansion in regions such as Asia and Northern Europe could trigger capital repatriation, strengthening local currencies and lifting long-neglected equity markets.

- Active opportunity: While not as extreme as the immediate post-pandemic period, valuation gaps outside the US remain historically wide, presenting an opportunity for bottom-up active managers.

In his 2005 commencement address, “This Is Water”, David Foster Wallace tells a simple parable. An old fish greets two younger fish by saying, “How’s the water?” They swim away asking themselves, “What is water?” It’s a profound message: The most pervasive and important realities in our lives are often the ones we fail to notice. The same is true in investing. The market environment can become so familiar that it almost becomes invisible.

The water we’ve been in

For well over a decade, that “water” has been defined by a specific global dynamic: a world of mercantilist policies, cheap currencies, and export-led growth. Many regions – most notably in Asia and parts of Europe – have run policies designed to maintain competitive currencies and subsidise exports. Those exports were largely aimed at the US, with surplus dollar earnings flowing back into US asset markets.

The result was a powerful self-reinforcing cycle. Capital inflows into the US pushed up asset prices and drove down interest rates. Lower rates fuelled a fiscal boom, stimulating imports and further deepening the trade and capital imbalance. The dollar and US assets strengthened in tandem, rewarding investors who rode the trend.

Passive investing thrived in this environment. With US markets and the dollar seemingly locked in a perpetual uptrend, the path of least resistance for global capital was into the US. That was the water we all swam in.

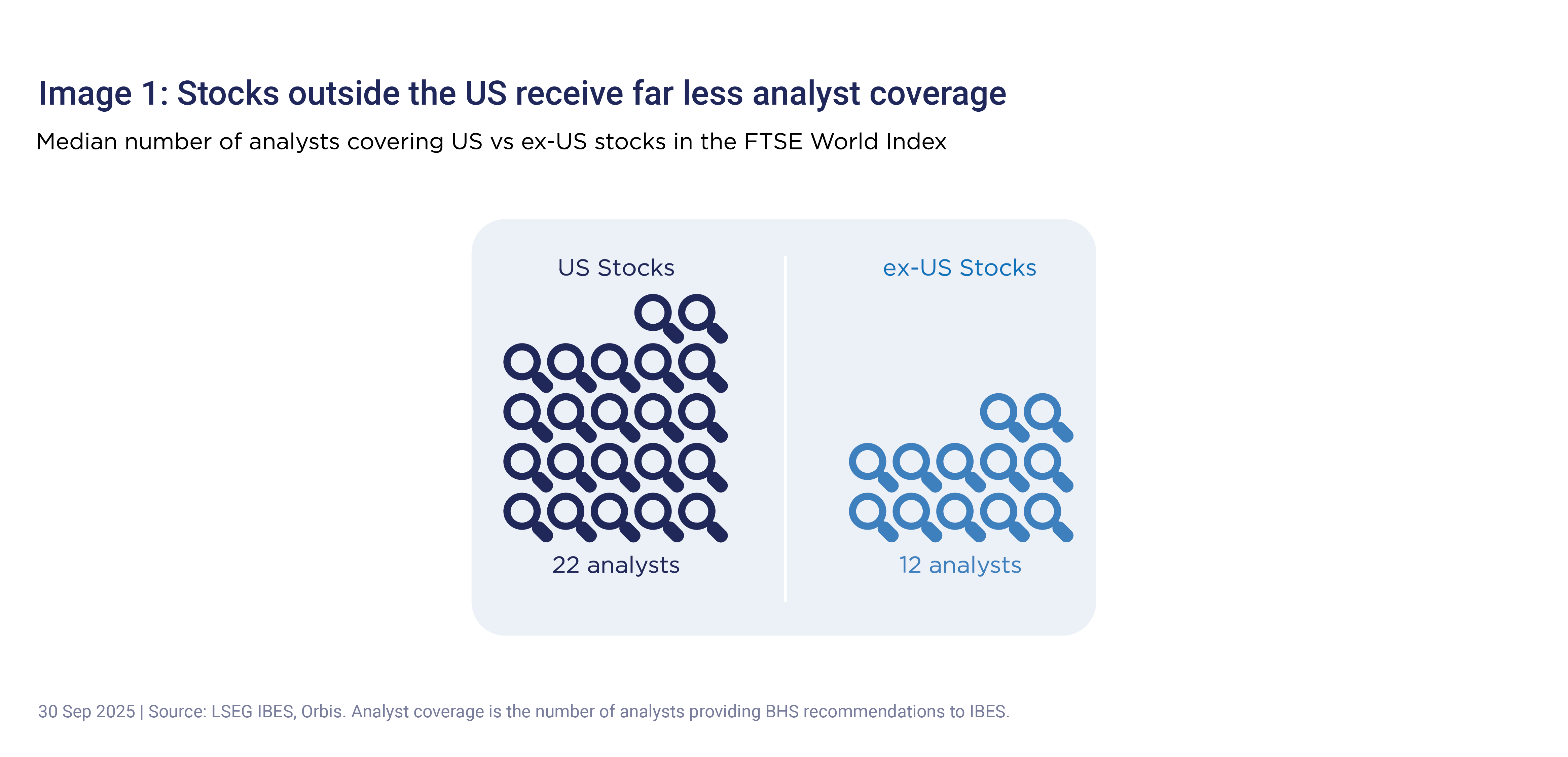

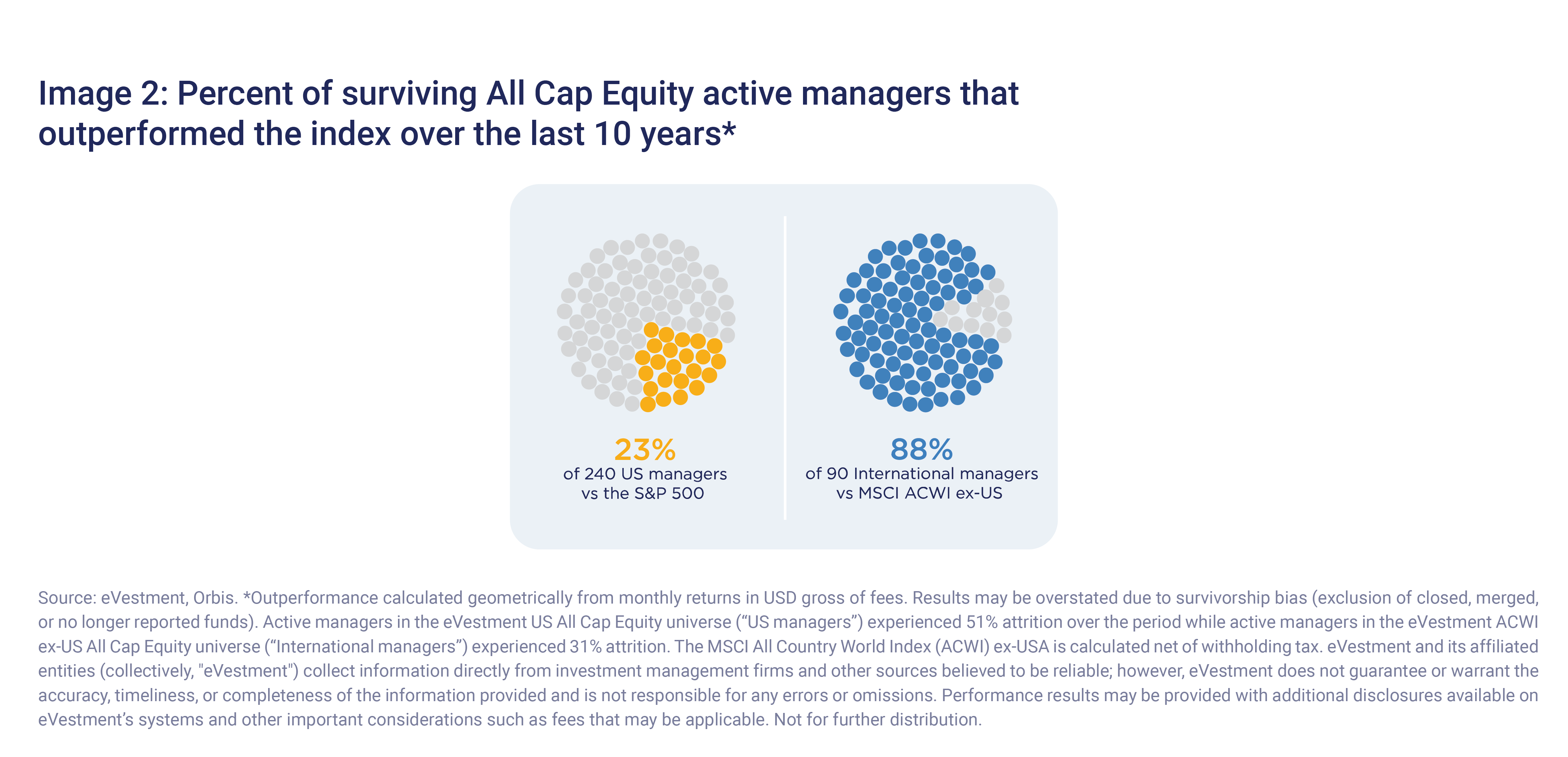

Given the lack of eyeballs on ex-US markets over the last decade, markets are rife with inefficiency and therefore opportunity for active management.

How the water is changing

But water doesn’t stay still. The environment has shifted dramatically. Policy in the US has turned inward, emphasising domestic industrial revival and strategic tariffs. This marks a structural break from the old regime. Export-led growth models are harder to sustain when the main destination market becomes more self-sufficient.

For the export economies, this change forces adaptation. If they can no longer rely solely on US demand, they will need to stimulate their own. Rather than flowing abroad, vast pools of domestic savings may now be redirected inward towards investment, fiscal spending and local consumer demand.

This has significant implications for investors. Global portfolios are still heavily concentrated in US assets and the dollar – an understandable legacy of the last cycle, but potentially a dangerous one if the tides are turning. Outside the US, assets and currencies remain cheap – a “double discount”. Now, they may also have a catalyst: a reversal in the capital cycle, as money begins to flow back home. Fiscal expansion in regions such as Asia and Northern Europe could strengthen local currencies and lift long-neglected equity markets.

As demonstrated in Image 1 and 2, given the lack of eyeballs on ex-US markets over the last decade, markets are rife with inefficiency and therefore opportunity for active management. Indeed, an active lens is essential given the complexity involved with investing across dozens of markets with wildly different economic, political and regulatory regimes. While not as extreme as the immediate post-pandemic period, valuation gaps outside the US remain historically wide. In other words, the water may be changing – and with it, the direction of capital and opportunity.

This article forms part of Orbis’ Six courageous questions for 2026. Explore more insights from the series:

- What if the real American exceptionalism now lies beyond America’s biggest stocks? by Simon Skinner

- Is the world’s safest currency actually the riskiest? by Nick Purser

- Which risk runs deeper: owning or avoiding emerging markets? by Stefan Magnusson

- Is AI a bubble, or is the best yet to come? by Ben Preston

- What if Trump is right? by Alec Cutler