The Paris Agreement sets out a global framework to avoid dangerous climate change by limiting global warming to well below 2°C and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. It also aims to support countries as they strengthen their ability to deal with the impacts of climate change. Vuyo Nogantshi explains the role of carbon pricing in these efforts.

The Paris Agreement suggests that to achieve the objective of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, global carbon emissions need to decline by about 45% by 2030 and reach net zero around 2050. By capturing the external costs of carbon emissions and tying them to their sources, carbon pricing is increasingly seen as an effective tool to achieve this objective and achieves two important outcomes:

- It shifts the burden for the damage back to those who are responsible for it and in a position to reduce it – the “polluter pays” principle.

- It gives an economic signal, and polluters can decide for themselves whether to discontinue their polluting activity, reduce emissions, or continue polluting and pay for it.

As a tool, carbon pricing captures the external costs of greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions, factoring in the toll the emissions take on the environment and the public, including increased healthcare costs, agricultural damage, and damage to property as a result of erratic climate change-related events. Carbon pricing ties these emissions back to their sources through a price, usually in the form of a price on the carbon dioxide emitted.

There are two main types of carbon pricing:

- Emissions trading system (“ETS”)

ETS (also known as cap and trade) caps the total level of GHG emissions and allows those industries with low emissions to sell their extra allowances to larger emitters. This helps ensure that the required emission reductions will take place to keep the emitters (in aggregate) within their pre-allocated carbon budget.

- Carbon tax

Carbon taxes directly set a price on carbon by defining a tax rate on GHG emissions or, more commonly, on the carbon content of fossil fuels. The emission reduction outcome of a carbon tax is not pre-defined, but the carbon price is.

Carbon crediting mechanisms are a third, less mainstream form of carbon pricing and allow emitters to purchase tradable credits from those who are implementing approved emissions reduction and can also be used for compliance if allowed by regulations.

Carbon pricing trends

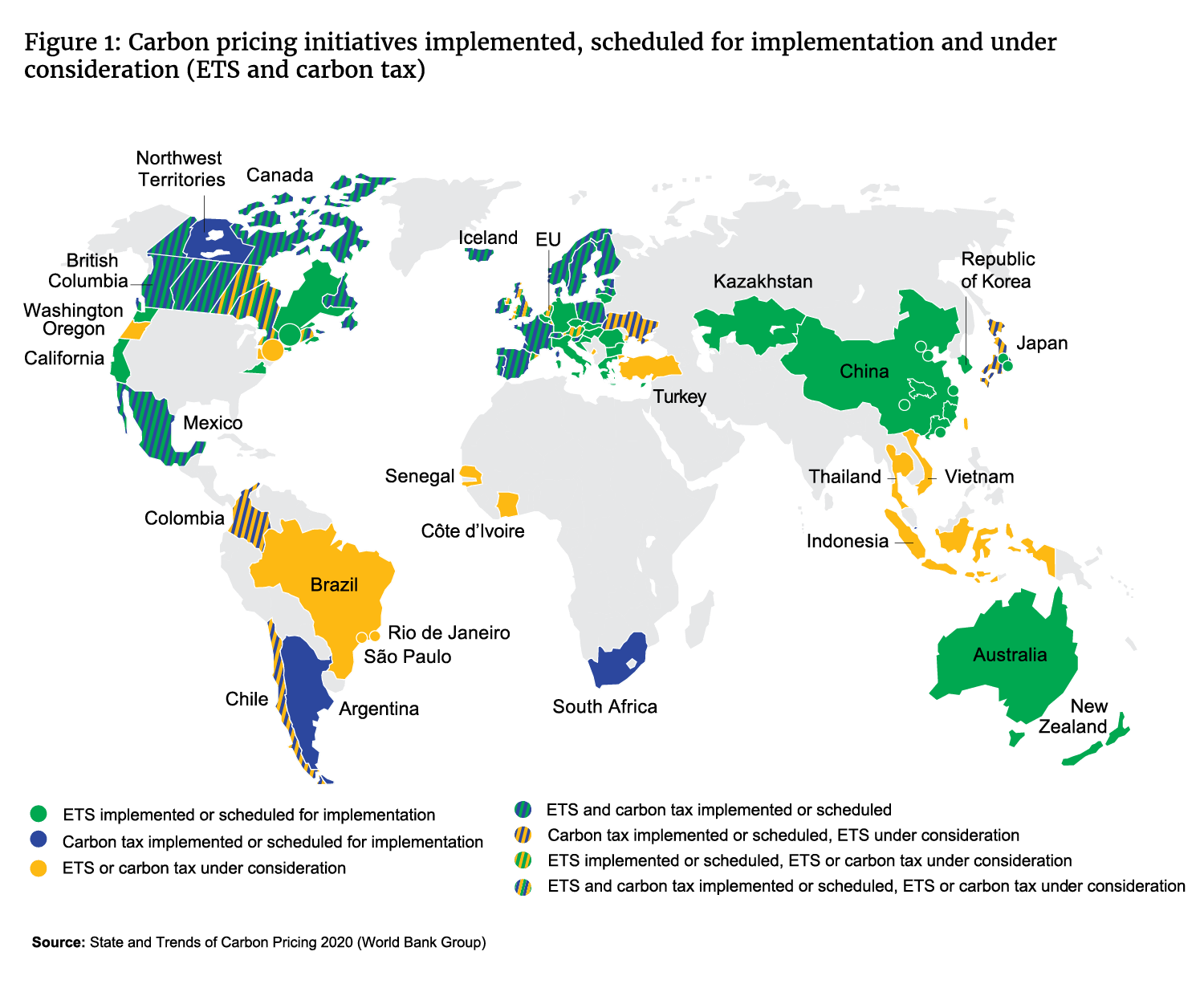

Carbon pricing has become increasingly popular among governments. According to the World Bank Group’s State and Trends of Carbon Pricing report, in 2020, there were 61 carbon pricing initiatives in place or scheduled for implementation, consisting of 31 ETSs and 30 carbon taxes, covering 46 countries and 22% of global GHG emissions (see Figure 1). This is compared to 10 years ago, when there were 19 carbon pricing initiatives covering 5% of global GHG emissions.

Governments raised more than US$45 billion from carbon pricing in 2019, representing both a revenue collection mechanism and an estimate of the absolute cost of covered emissions. According to the Global Carbon Account 2020, almost half of the revenues were dedicated to environmental or broader development projects, and more than 40% went to the general budget. The remaining share was dedicated to tax cuts and direct transfers.

The Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, which brings together leaders from government, private sector, academia and civil society to expand the use of carbon pricing policies, launched the High-Level Commission on Carbon Pricing and Competitiveness at its 2018 High-Level Assembly. Despite carbon prices increasing in many jurisdictions, the Commission has indicated that they remain substantially lower than those needed to be consistent with the Paris Agreement. An appropriate carbon price should be determined by local conditions, the role the carbon pricing instrument should play, as well as the impact of other climate policies and technological progress. Equally, jurisdictions may choose to implement a tax or an ETS with an initially low price that rises over time as companies become familiar with the new pricing policy.

Nevertheless, we can expect carbon prices to increase as various jurisdictions find themselves pressed to fulfil their commitments to meet Paris Agreement goals.

Internal carbon pricing reduces emissions across value chains

In 2019, a report from the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) indicated that about 1 600 companies disclosed that they currently use internal carbon pricing or that they anticipate doing so within two years. With an increasing number of companies committing to net-zero targets and growing investor pressure, the use of internal carbon pricing to reduce supply chain emissions is likely to grow in the future. This is likely to be used as a risk management tool to reflect the actual or expected carbon taxes in the jurisdictions within which businesses operate and should aid business decisions.

Companies, especially those in high-emitting sectors, that are under-pricing or not utilising internal carbon pricing are less likely to respond effectively to climate events or regulatory changes in the short to medium term. They are also more likely to suffer, rather than gain, from the transition to a low-carbon economy over the longer term.

A tool for responsible investors

The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (“TCFD”) was created in 2015 by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to develop consistent climate-related financial risk disclosures for use by companies, banks and investors in providing information to stakeholders. As climate data for public companies becomes more widely available and increasingly standardised through regulation developed by bodies like the TCFD, investors will be better positioned to quantify the actual and potential financial impact of climate-related factors on the intrinsic values of companies and evaluate the soundness of their risk management plans.

While there are cases of temporary setbacks, over the long term there is really only one way carbon pricing can go: higher. High carbon intensity assets are likely to become less competitive sooner as carbon prices increase globally, which is unanimously viewed as the most essential policy tool to achieve the energy transition. Therefore, evaluating companies, especially those in high-emitting sectors, would seem incomplete without considering carbon pricing.

A panel of local and global thought leaders will be discussing carbon pricing and many other ESG-related topics at the virtual Allan Gray Investment Summit on Tuesday, 14 September 2021. If you have not registered for this event yet, please email info@investmentsummit.co.za or call us on 021 415 7499.